The making of the world’s most ambitious master plan

By WATG

November 24, 2020

To grasp the scope of The Red Sea Project on Saudi Arabia’s west coast, imagine creating a plan for developing 28,000 square kilometers before anything – roads, power, drinking water – existed there.

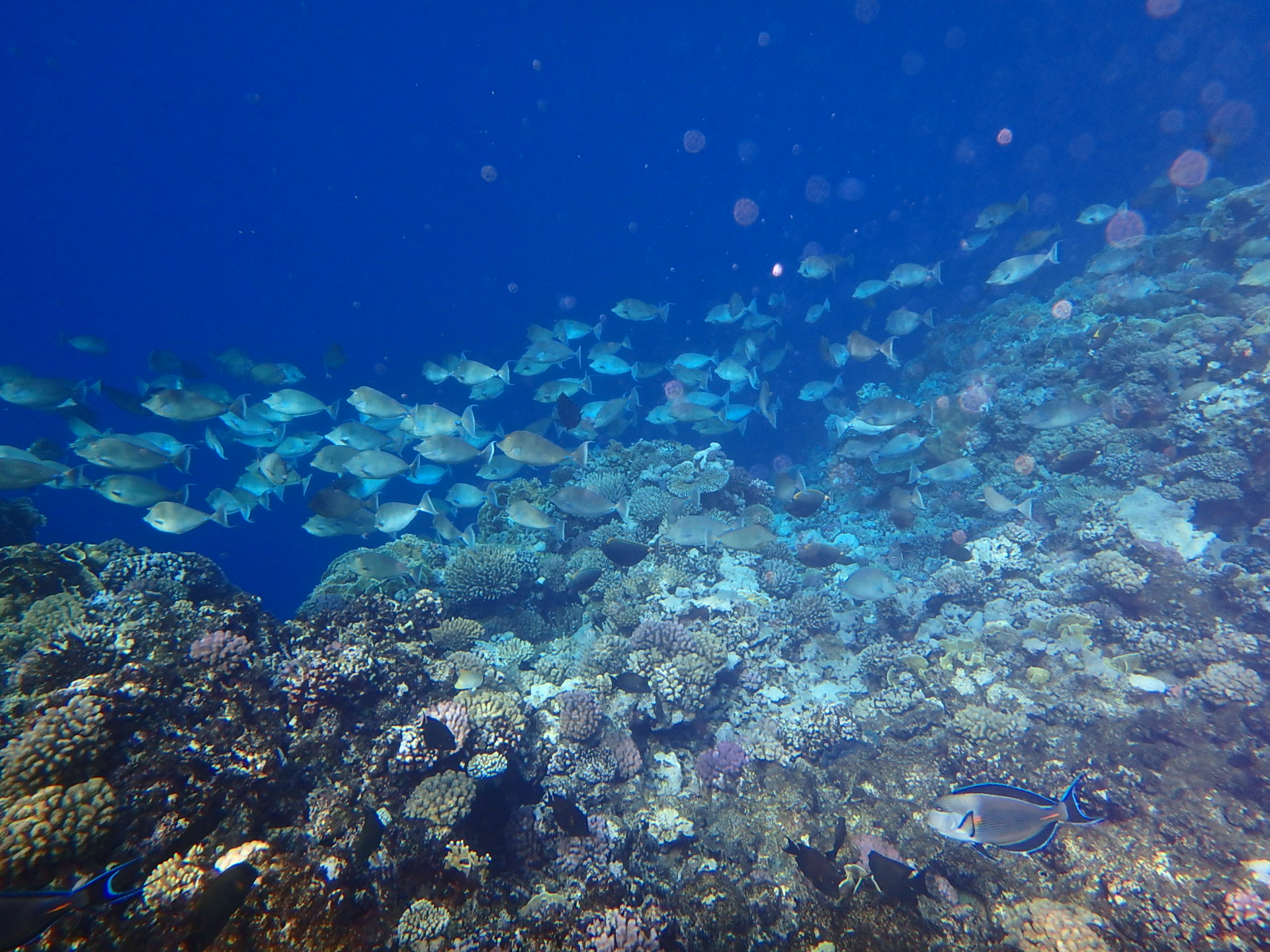

Then layer on top of that vision an archipelago of 90 islands, each with a unique landscape, hundreds of miles of coastline and a couple of dozen interlocking ecosystems, many critical, including coral reefs florid with marine life and the mangroves that created the fragile strands of land.

That’s what faced WATG’s integrated design team – Bryan Algeo, Lance Walker and Christopher Craig – when they stepped onto the scene to begin work.

“I’d never done anything to this scale before,” Craig says. “It was like doing all of the Hawaiian Islands at once pretty much from scratch.”

Labeled a “giga project” because of its size, the development is one of the most ambitious luxury undertakings in the world, bringing visitors to a hidden gem, a barely touched area rich with biodiversity and fragile ecosystems. It’s the cornerstone of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 program, which aims to make the country a global force in tourism.

The development is one of the most ambitious luxury undertakings in the world, bringing visitors to a hidden gem, a barely touched area rich with biodiversity and fragile ecosystems.

The WATG Red Sea Project team on a site visit

The WATG team learned in January 2018 that they’d won an intense global competition to develop the master plan for the project, a master plan unlike any other in its focus on preserving the region’s exquisite ecosystems while creating an unparalleled luxury destination.

That began an exhaustive exploration of the site, its considerable natural charms, and a long, engaged dialogue and partnership with The Red Sea Development Company (TRSDC) over how to protect unspoiled ecosystems while giving visitors an experience found nowhere else.

In six months, the team that eventually grew to hundreds created a plan putting the environment first, deciding not to lay a human hand on more than 75 percent of the islands. Plans now anticipate developing up to 22 islands with 50 hotels and 8,000 rooms by 2030 with 2,500 of them on Shurayrah, a hub island just off the coast. Phase One, set for completion in 2023, will feature 16 hotels with 3,000 rooms.

“The ambition is to create a 30% net conservation impact through the development and to exceed what would be the goals and economical outcomes of this area if it was just declared a national park.”

Along the way, Craig alone logged 4,000 hours and numerous trips to the site, oftentimes traveling in boats piloted by local fishermen who knew how to navigate the maze of coral reefs, the world’s fourth largest barrier system, and breakwaters. He and the team waded through tides to islands featuring everything from wide beaches to leafy thickets and sand-swept interiors. Environmental and energy experts from engineering firm Buro Happold and King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) joined TRSDC in the exploration of the islands. Hundreds of choices were made about what to develop where, which islands to make low-density luxury destinations and which islands could support more extensive amenities and hotels. And, by necessity, he created a new way to keep track of the development opportunities across a vast area and share it with The Red Sea Development Company, using of all things, Google Earth. Analyzing 28,000 km2 of land and water, this turned out to be the best way to understand the islands, coast and land and keep track of distances.

“The ambition is to create a 30% net conservation impact through the development and to exceed what would be the goals and economical outcomes of this area if it was just declared a national park. This is a really ambitious goal and it has changed my vision of what role the private sector can play in driving towards a healthy ocean,” says Carlos Duarte, Professor of Marine Science at KAUST and a key member of TRSDC’s Advisory Board.

The Red Sea Development Company began the planning process with a goal of 20,000 rooms and amenities in the area. By the time Craig and the team with KAUST, Buro Happold and Applied Technology & Management (ATM), had finished, that number was under 12,000. “They reduced the program by 40 percent,” Craig says. “That’s because they had a fuller understanding of the sensitivity and carrying capacity of the region that we helped them figure out.”

Video courtesy of The Red Sea Development Company

That understanding evolved over time and under deadline with each visit unveiling new insights about the area’s treasures. Over time, for instance, the team realized the tides change with the seasons and the beaches move so putting a hotel in one place might work in winter, but not in the summer. Over time, they came to understand the importance of the lagoon and flushing by winds and water. Working alongside KAUST and Buro Happold, they charted the highly sensitive nesting sites of turtles, including the critically endangered Hawksbill, and learned the importance of the region as a migratory path for dozens of types of birds. They mapped not only the landmass of each island but the benthic habitats a kilometer into the water to understand those vital transition areas.

The first site information started flowing the second month of working on the plan, but the analysis continued for the entire nine months. There were two dozen ecosystems to consider. “It was really understanding what the critical ones were,” he says.

The Red Sea Development Company team brought in Philippe Cousteau, the grandson of Jacques Cousteau, the legendary explorer and filmmaker, and other experts to better understand coral and mangrove ecosystems. Mangroves trap sediment and the reefs protect the resulting islands from storms. “It was sensitivity training which changed our opinion on not disturbing mangroves to create beaches and it led to largely leaving the perimeter of the islands alone,” Craig says.

Coral and mangroves weren’t the only critical ecosystems. There was seagrass, which improves water quality, provides food and habitat and generates oxygen through photosynthesis. “Seagrass is the aquatic forest that, with the mangroves, is the lungs of the lagoon and it creates the habitat to attract a variety of animals,” he says. They examined turtle nesting sites and set aside nine islands as nature reserves and many more islands as undeveloped.

The site’s unique topography and eco-systems pose challenges that are met with even greater opportunity

“The trick is to really understand the site, understand the environment, really have a clear picture of what you’re trying to accomplish with the development.”

Then there were the beaches on 90 islands to map and analyze. Ultimately, they decided only 22 should be touched and those were evaluated using a long list of considerations, starting with the environmental impacts. “Each island had its own decision-making process,” Craig says. One island with a stunning ecosystem went from thousands of rooms to only a few hundred.

What Craig found on repeated visits was not only the fragility of some islands, but the wide variance in seasonal tides because the area is so flat. Months into the project it became clear the shorelines in some places could change by 300 meters depending upon the time of the year. “You could go to one place that was really beautiful during a high tide and come back at low tide and it’s a quarter mile from the water,” Craig says. “How’s that going to work?”

So, the tidal change on each island became another branch on an already-complicated decision-making tree. They ended up putting into the mix for islands the seasonal high, high tides, the low, low tides, and the average high and low tides. That data not only contributed to what island to develop and where to place hotels but where to place overwater villas, one of the project’s attractions. With many areas barely above sea level, the projected rising sea level and increased storm surges caused by the climate crisis had to be considered.

Tidal zones, benthic mapping, turtle nesting sites, fragile corals, seagrass, mangrove habitats, sea level rise and storm protection, potential infrastructure sites and navigation channels to move people throughout the islands. Where could the necessary infrastructure, including water desalination and power, go? How would visitors get around the area?

The data sets kept multiplying. So, Craig and the WATG team turned to an innovative solution: Geographic Information System (GIS), a digital framework capable of gathering, managing and analyzing data across the vast areas of the site. “That’s the software that saved us. We ended up not only inputting all the survey and environmental information, but all the details of the master plan organized by island and parcel,” he says.

The Red Sea from above

Xin Li, also on the planning team, was WATG’s GIS super-user who created a database that would allow the team to see all the islands being considered for the master plan. They soon realized there wasn’t one master plan, but 22 for each of the islands to be developed. Each island in the program was assigned a population and a number of units and a mix of hotels – lifestyle, retreat, wellness. “We could keep track of it that way,” Craig adds. “It became our Bible for six months, where one click on an island reveals the parcels and a click on a parcel unveils all the improvements.”

“By the end, we could say with confidence this is a plan we can stand by that achieves the best compromise across many conflicting factors but makes no compromise to the goal of enhancing the natural environment.”

While team members were focused on individual destinations, compiling the information on GIS and Google Earth, Craig was able to see the big picture. “We could think about it at a holistic level, how it was all fitting together, because that’s hard to understand with the scale of the project,” he adds.

For Craig, the process created a path to an enlightened environment-first plan that created a range of authentic natural experiences for guests and visitors.

“The trick is to really understand the site, understand the environment, really have a clear picture of what you’re trying to accomplish with the development,” he says. “I liken it to sculpting a big block of rock. It gradually reveals itself as you get in there and you see the fault lines and you see how you can shape places that make sense. By the end, we could say with confidence this is a plan we can stand by that achieves the best compromise across many conflicting factors but makes no compromise to the goal of enhancing the natural environment.”

An underwater view of one of the site’s reefs

Latest Insights

Perspectives, trends, news.

- News |

- Trends

Interior Design Trends 2025: Emotional, Experiential, and Environmentally Conscious Spaces

- News |

- Trends

Interior Design Trends 2025: Emotional, Experiential, and Environmentally Conscious Spaces

- Strategy & Research |

- Trends

2025 Outlook: WATG Advisory predicts the top hospitality trends.

- Strategy & Research |

- Trends

2025 Outlook: WATG Advisory predicts the top hospitality trends.

- Employee Feature

Unlocking Value & Vision: Guy Cooke & Rob Sykes Discuss WATG Advisory’s Bespoke Approach

- Employee Feature

Unlocking Value & Vision: Guy Cooke & Rob Sykes Discuss WATG Advisory’s Bespoke Approach

- Case Study |

- Design Thinking & Innovation

In Conversation: Marcel Damen, General Manager of Rissai Valley, a Ritz-Carlton Reserve

- Case Study |

- Design Thinking & Innovation