Designing Hotels for the People’s Republic of China (Part I)

By WATG

December 10, 2015

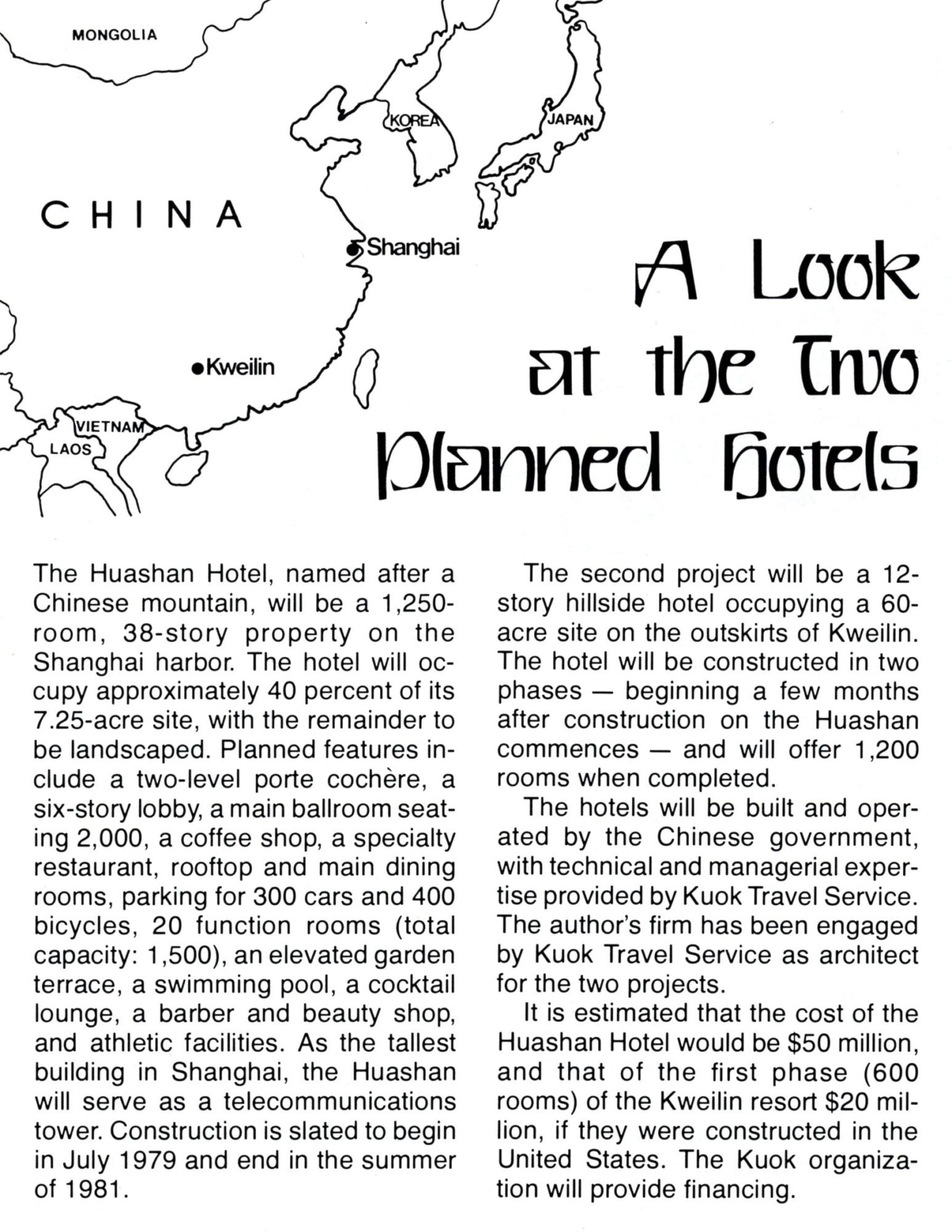

As part of our 70th Anniversary celebration, we’ll be revisiting past articles and interviews of our founders and past employees of WATG. The following is part 1 of an article written by Greg Tong published in the May 1979 issue of The Cornell H.R.A. Quarterly. Greg shares his experience of being the first Western architect to do work in the People’s Republic of China (before diplomatic relations were established). The Huashan and Kweilin hotels were never built. Click here for Part 2.

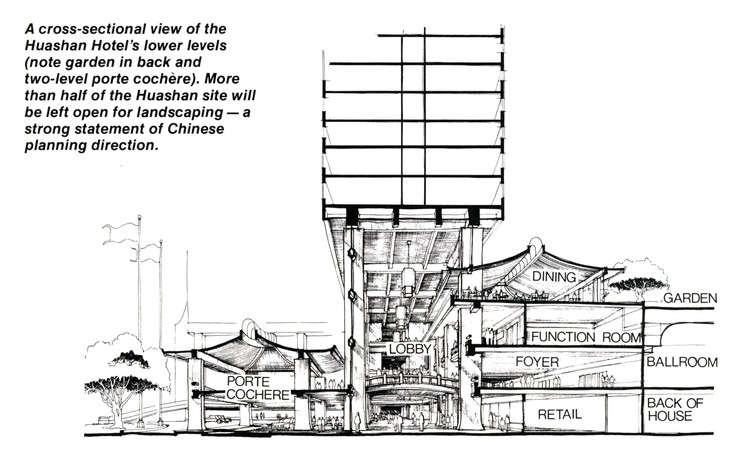

Among the facilities we recently incorporated into our design plans for a proposed hotel were many conventional amenities: a cocktail lounge, a coffee shop, a swimming pool. But the Huashan Hotel will also boast such features as an underground air-raid shelter, parking for 400 bicycles, and living quarters for 300 staff members–because it will be constructed in the People’s Republic of China, where design must reflect ways of thought and styles of living radically different from our own.

Many of the apparent peculiarities included in our design plans for the Huashan Hotel are easy to understand once one knows a little about present-day Chinese culture and how it differs from our own.

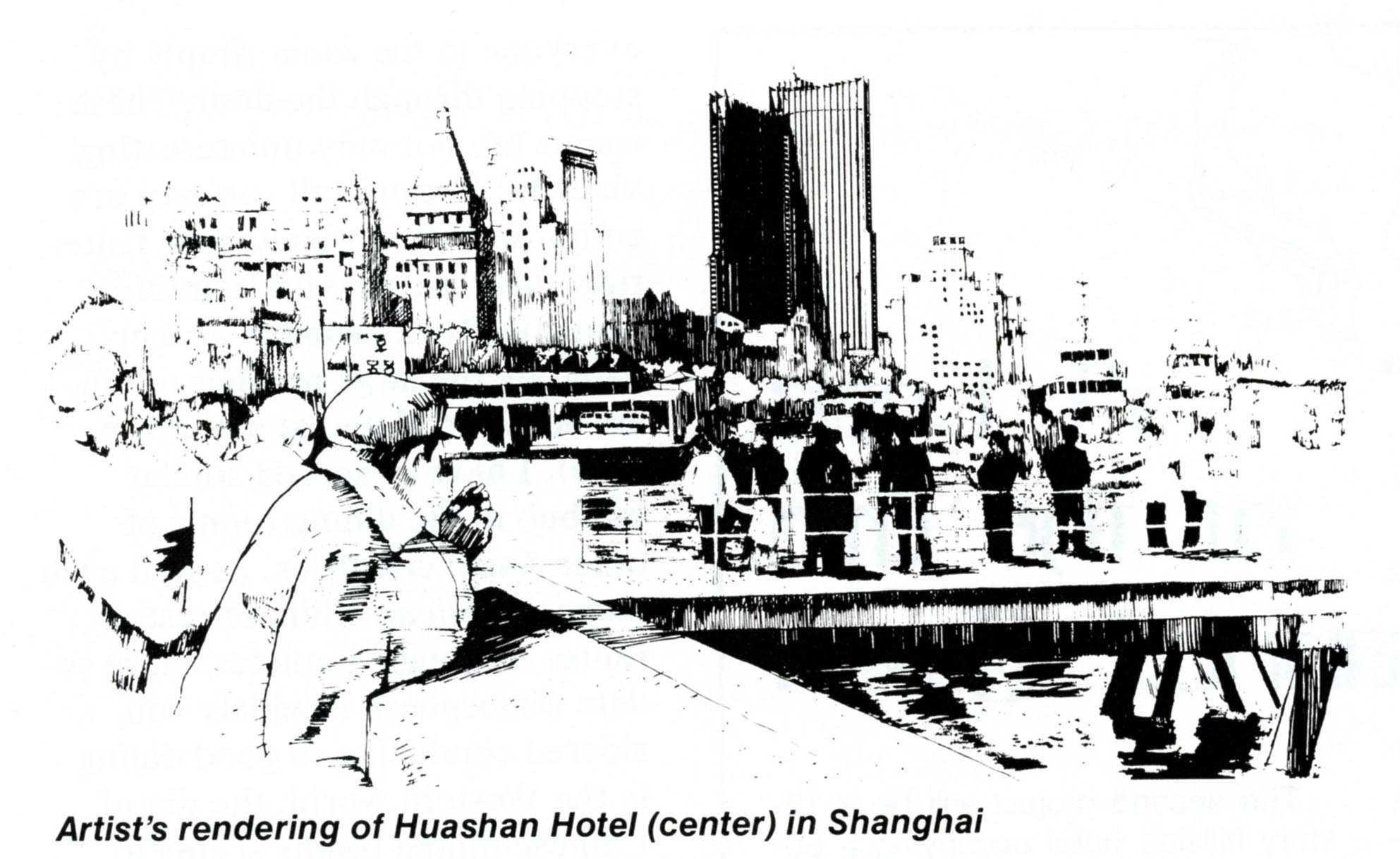

In undertaking the design of two Chinese hotel–Shanghai’s Huashan Hotel and a Kweilin resort property, whose more conventional features and construction plans are described below (see image) we had much to learn about the current state of Chinese technology and, more important, about Chinese attitudes. In the following paragraphs I will comment on some of the factors pertinent our design decisions, with an occasional aside on life today in this little-known nation.

Dorms to Disco

Many of the apparent peculiarities included in our design plans for the Huashan Hotel are easy to understand once one knows a little about present-day Chinese culture and how it differs from our own.

In a typical Western hotel, onsite housing is often provided for such upper-level personnel as the general manager, assistant manager, executive chef, and director of housekeeping. In China, quite the reverse is true: on-site housing is provided for unmarried busboys, waitresses, and so forth.

The severe housing shortage in China is one reason so much space has been allocated for staff members’ living quarters in the Huashan Hotel.

The severe housing shortage in China is one reason so much space has been allocated for staff members’ living quarters in the Huashan Hotel. The typical urban family (comprising at a minimum husband, wife, and two children) is generally assigned what we consider a one-bedroom apartment, with the children sleeping in the living room. The chances of a single young adult enjoying the luxury of his own apartment–so common in the United States–are quite slim; most single adults, and many young married couples without children, live with their parents. The individual able to find housing elsewhere relieves some of the congestion in his parents’ apartment.

Another factor necessitating a facility for staff housing is the assignment of work hours. Individuals assigned to the early-morning shift must often be on the premises by 4 AM to begin breakfast preparation and similar duties. If the worker lives a considerable distance from the hotel, he has no easy means of getting to the property at that hour: few adults own cars, and public-transportation services generally do not operate so early. Hence, the provision of on-site housing for workers is a matter not of convenience but of necessity.

Because elevators are considered a luxury, the building used by a hotel for staff housing is often only four to five stories high an occupies a fair amount of ground space. By contrast, the hotel itself–with elevators for guest use–might be a 20-story highrise occupying far less ground space. Staff living quarters often take the form of dormitories, with four to 30 persons in a room and communal bathroom facilities (the sexes are segregated either by wing or by floor). In some cases a bed is assigned not to an individual but to a job or shift (e.g., to the early-morning shift, rather than to the individual who works it).

As noted above, the private automobile is a relative rarity in China, and most Chinese citizens use either bicycles or public buses as their means of transport. The popularity of bicycles has been reflected in our plan for extensive bicycle-parking space at the Huashan Hotel. (It is interesting to note that when a bicycle is stolen–a very infrequent occurrence, by Western standards–the rider is given another until his own is recovered.)

The Chinese require that an underground air-raid shelter be a part of every major new building constructed. Such shelters are intended primarily for the wartime use of staff members and area residents (it is assumed there would be few hotel guests under conditions of national emergency). The shelter requirement is a precautionary national policy; it is both possible and desirable to make other use of the shelter space during times of peace. We have suggested that the Huashan Hotel’s shelter be used for bowling and disco dancing; it could quickly be converted from these uses back into an air-raid shelter if necessary.

Dining: Dimension and Din

Another unusual aspect of the Huashan Hotel’s design is the dining capacity, which is sufficient to serve 100 percent of the hotel’s guests at a single seating.

Another unusual aspect of the Huashan Hotel’s design is the dining capacity, which is sufficient to serve 100 percent of the hotel’s guests at a single seating.

The rationale for this impressive capacity embraces both Chinese tradition and practical considerations.

The evening meal has traditionally been the focal point of the Oriental day, a time for the clan to gather and share conversation. To take a meal by oneself, as Westerners often do, would be considered a disrespect to the family. This thinking has made its way into Chinese hotel operations, which generally offer a dining room capable of seating all the hotel’s guests simultaneously, supplemented by an unusually large number of function rooms for smaller tour groups and VIP groups.

Moreover, because most hotel guests in China are members of organized tour groups, arriving and departing on a single schedule, hotels usually have no choice but to feed large numbers of guests simultaneously. (Visitors are generally assigned to a specific table in the dining room and are expected to sit at that table for the duration of their stay.) Chinese facilities do not offer the number or variety of specialty restaurants we are accustomed to finding in Western properties.

Despite the often extraordinary capacity of the dining facilities, Chinese hotels are characterized by a much higher ratio of kitchen area to dining space than Western properties are. At present, Chinese hotels are labor-intensive, with two or three times as many staff workers per guest as one would encounter in the United States. Kitchens and associated service areas must therefore be quite large simply to accommodate the worker traffic.

The considerable quantity of work space required is partially accounted for by the nature of Chinese cuisine, which entails a great deal of painstaking preparation–cutting meat and vegetables into small pieces, for example. It is not unusual to find a large number of staff members whose task it is to sculpt vegetables into flower shapes and miniature animal designs–or to find a room full of workers engaged in such pursuits as carving an intricate garden scene into the skin of a melon.

The spacious dining rooms have very high ceilings and are invariably rectangular, with little attempt to achieve a degree of privacy in corners or through the use of room dividers; one can gain a view of everyone in the room simply by stepping through the door. These rooms are not only uninteresting visually: because all surfaces are composed of relatively hard materials, they are also undesirable acoustically (a problem exacerbated by the large number of diners accommodated at any given time). I have observed similar hubbub in the dining rooms of other Asian countries, as well as in some American Chinese restaurants. Although a quieter, more sedate atmosphere is widely considered conducive to good dining in the Western world, the din of Chinese dining rooms seems to have no detrimental effect on diners’ appreciation of the meal–in fact, the noise appears to be equated with enjoying oneself.

Latest Insights

Perspectives, trends, news.

- Employee Feature |

- Inside WATG

Design Discourse: 5 Words of Inspiration

- Employee Feature |

- Inside WATG

Design Discourse: 5 Words of Inspiration

- News

Biocultural Conservation: Bridging Science and Design

- News

Biocultural Conservation: Bridging Science and Design

- Strategy & Research

Wimberly Interiors’ Interpret British Design: Eclectic, Modern with a Twist, Bespoke

- Strategy & Research

Wimberly Interiors’ Interpret British Design: Eclectic, Modern with a Twist, Bespoke

- Employee Feature

In Conversation: Sean Harry & Dan Hinch: The Intersection of Digital Practice & Landscape Architecture.

- Employee Feature